An Unsung Hero Of Paris – The Life & Work Of Comte de Rambuteau

Who is the true hero of the transformation of Paris during the 19th century? Although much (deserved) credit is given to Napoleon III and his prefect Baron Haussmann for reshaping Paris from a jumbled medieval city into a modern mecca, there's little praise for the visionary who did the initial heavy lifting.

Creating a Modern City

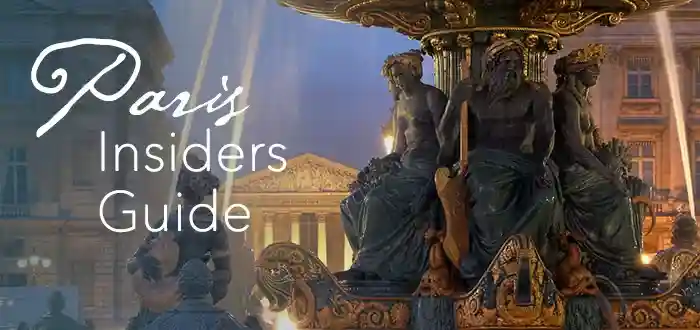

The street named after the comte – Rue Rambuteau & Les Halles in the 19th century, Wikimedia

The street named after the comte – Rue Rambuteau & Les Halles in the 19th century, Wikimedia

It's likely that you've never heard of Comte de Rambuteau, but he's the man we should tip our beret to for turning Paris from a collection of cholera-ridden ghettoes into a modern, vibrant, and clean city. Sure, there's a Metro station and a street named for him in the Marais, but not enough is written about Rambuteau. Let's learn about the man who, when he came into office, said his goal was to provide Parisians with "clean water, air, and shade".

![]()

Before Haussmann There Was Rambuteau

The Metro station named after the street that was named after Claude-Philibert

The Metro station named after the street that was named after Claude-Philibert

Claude-Philibert Rambuteau was prefect of Paris under Louis Philippe I. (Louis Philippe was the "I" and only, since he ended up being the last king of France.) Rambuteau took office in 1833 and began an ambitious plan to improve the water supply of Paris by building new fountains and establishing an extensive water system. It was these efforts that made Baron Haussmann's later accomplishments possible. Essentially, Rambuteau laid the groundwork for the transformation of Paris that Haussmann would carry out decades later, under the Second Empire.

The Deadly Epidemic That Would Transform Paris

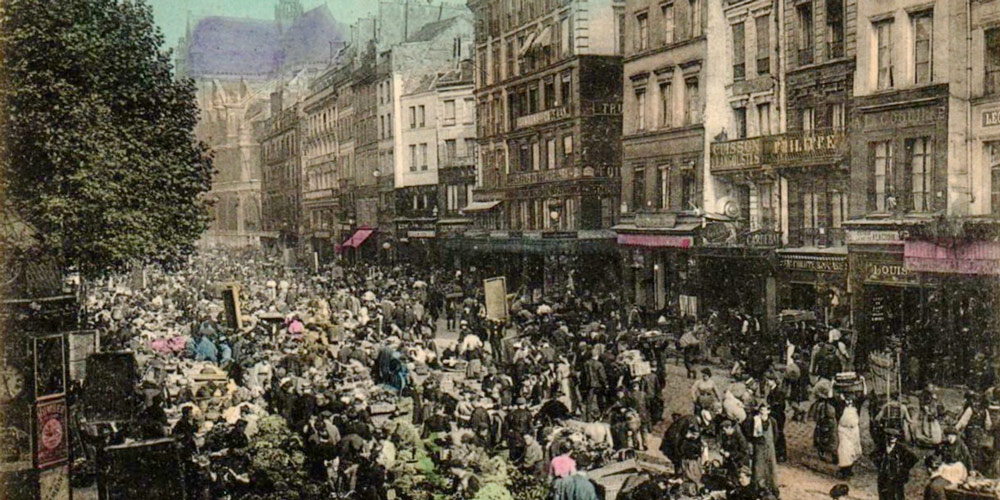

Notre Dame & environs in the later 19th century

Notre Dame & environs in the later 19th century

In March 1832, a major cholera epidemic hit Paris, as well as the rest of France, the UK, and even the US. A steady stream of cholera-infected citizens from every Paris arrondissement were sent to the Hotel Dieu hospital on Île de la Cité (in front of Notre Dame); most would die within a day or two. Over six months, the cholera epidemic would claim 19,000 lives in Paris and 100,000 in all of France. By April, the city smelled of death and the streets were choked with hearses.

No one knew at the time the cause of or the cure for the disease but there was plenty of speculation. One Paris official advised people to take a hot bath infused with vinegar, salt, and mustard to ward off the illness. In case you've forgotten Cholera 101, it is caused by a highly-contagious bacteria. Cholera is transferred by infected water or food contaminated with the bacteria. It's so powerful that these deadly organisms can survive in salt water and can contaminate any organism that has contact with it. It's no wonder early-19th-century Paris, with its narrow, windy streets, deplorable hygiene and lack of clean water, was a breeding ground for this bacteria.

A Classic Seine Dinner Cruise

A dinner cruise is one of the easiest ways to see Paris lit up at night without racing across town. This 2.5-hour cruise serves classic French cuisine on an all-glass boat, so the views stay with you as the landmarks slide by.

As If From a Jane Austen Novel Comes Our Hero

1754 map of Île de la Cité

1754 map of Île de la Cité

As if from the pages of a Jane Austen novel, the man who would save the day was appointed the prefect of Paris. Madame de Lamaratine wrote of Rambuteau —

"Thus it would seem that his heredity, his native soil, his family, all combine to endow him with what Montaigne calls une tete bien faite; a sound mind and a sound body, an even temper, keen and vigorous reasoning powers and a moral equilibrium. Add to these a simple and kindly disposition, a tendency to good-natured forbearance, an inflexible conscience, a rare capacity for work, and and intense love for his country...everything about him indicates nobility and loftiness of character and absolute integrity."

Taking office in 1833, a year after the cholera epidemic, Claude-Philibert Rambuteau decided to test hygienist theories — among them, that the disease was spread by urban crowding. His first job was to cut a swath through the center of Paris. Rambuteau believed the narrow, winding streets with poor access to clean water and deplorable sanitation conditions encouraged the development of cholera. He started by cutting thirteen-metre-wide roadways through Paris, starting with would become Rue Rambuteau. It was groundbreaking. This was the first time a wide road had been built through the maze that was central Paris.

While prefect of Paris from 1833 to 1848 Rambuteau created the groundwork for its transformation. Of course years later his successor during the Second Empire, the prefect Baron Haussmann, would apply Rambuteau's principles on a much larger scale. During Rambuteau's administration, many great things were accomplished including the completion of the Arc de Triomphe and the construction of the Champs-Elysées.

Day Trips From Paris

Some of France’s most memorable places lie just beyond Paris. Spend a day exploring royal chateaux, vineyard regions, medieval towns, and historic landmarks, then return to the city by evening with a richer sense of the country.

1,700 Fountains for Paris

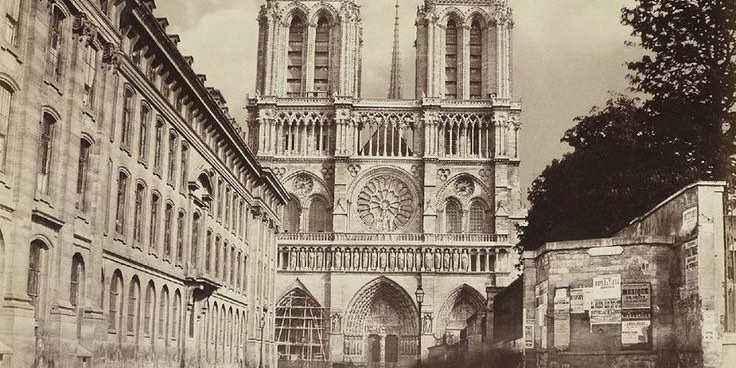

Fountain on Place de la Concorde, photo by Mark Craft

Fountain on Place de la Concorde, photo by Mark Craft

Rambuteau modernized the sewers of Paris and ordered the construction of hundreds of fountains. Many of these fountains are still functioning including the two fountains in the Place de la Concorde, the fountains along Champs-Elysées, the Fontaine Molière, the Fontaine Cuvier, and the fountain at Place Saint-Sulpice.

Claude-Philibert took his job seriously, building 1,700 fountains in Paris and 200 kilometers of new water mains. Most importantly, this meant monumental fountains would not just be ornamental, they would provide clean, drinking water to the people of Paris.

Top-Rated Food & Wine Experiences In Paris

Choose the culinary experiences that feel most like Paris. In our guide we highlight tastings and tours worth booking ahead, from cellar wine sessions to market walks, with clear notes on timing, size, and what sets each apart.

Let There be Light… And Shade

Rambuteau also developed gas lighting for Paris streets. When he began his role as the city administrator, Paris had 69 gas jets. By the time he left his post there were 8,600 gas jets.

To provide shade for Parisians on hot, sunny days thousands of trees were planted along the avenues. Heck, we can even thank Rambuteau for the famous (or infamous, and now departed) pissoirs of Paris. Although Rambuteau began these changes, he did not have the financial support from Louis Philippe to implement the grand work that Haussmann and his successors would eventually complete from 1850 to almost the end of the century.

Rambuteau was the hero who showed the way forward. So, the next time you're here, visit Rue Rambuteau or Metro Rambuteau and give a petit merci to the man who transformed Paris.

Paris Planning Guides

Top 10 Food Tours

Top 10 Food Tours |

Top Montmartre Hotels

Top Montmartre Hotels |

Getting Around

Getting Around |

Glorious Dinner Cruises

Glorious Dinner Cruises |

Discover What's On When You're Here• March 2026 Things to Do…• April 2026 Things to Do…• Easter in Paris…• May 2026 Things to Do…• June 2026 Things to Do…• Month-by-Month Calendar… |